Green Infrastructure as a Climate Action Planning Strategy for the Southwest

Climate Change

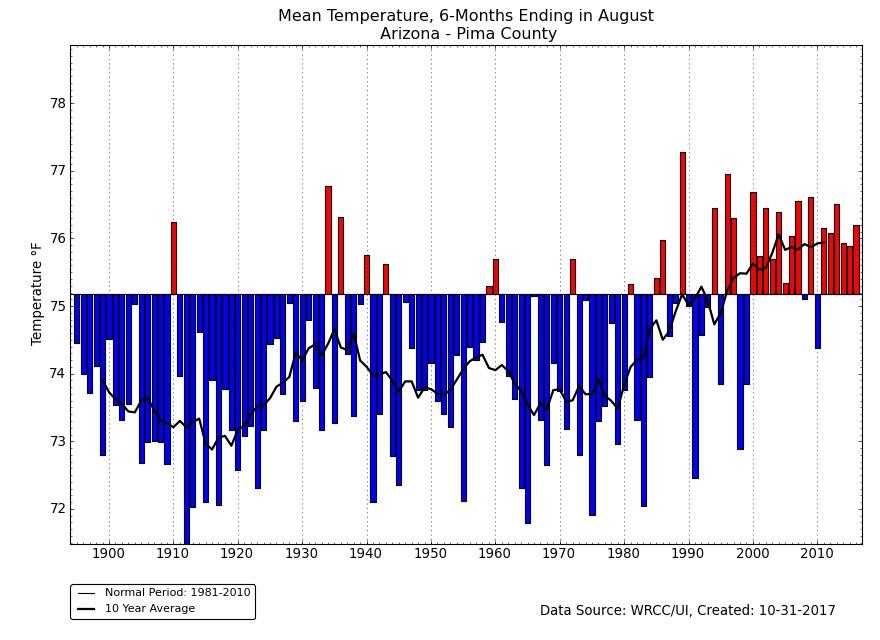

The climate of southern Arizona is characterized by a few notable extremes, excess heat and lack of water. For the Pima County in the State of Arizona, average mean temperatures have been steadily increasing for the past 30 years.

Figure 1: West Wide Drought Tracker, created: 10-31-2017

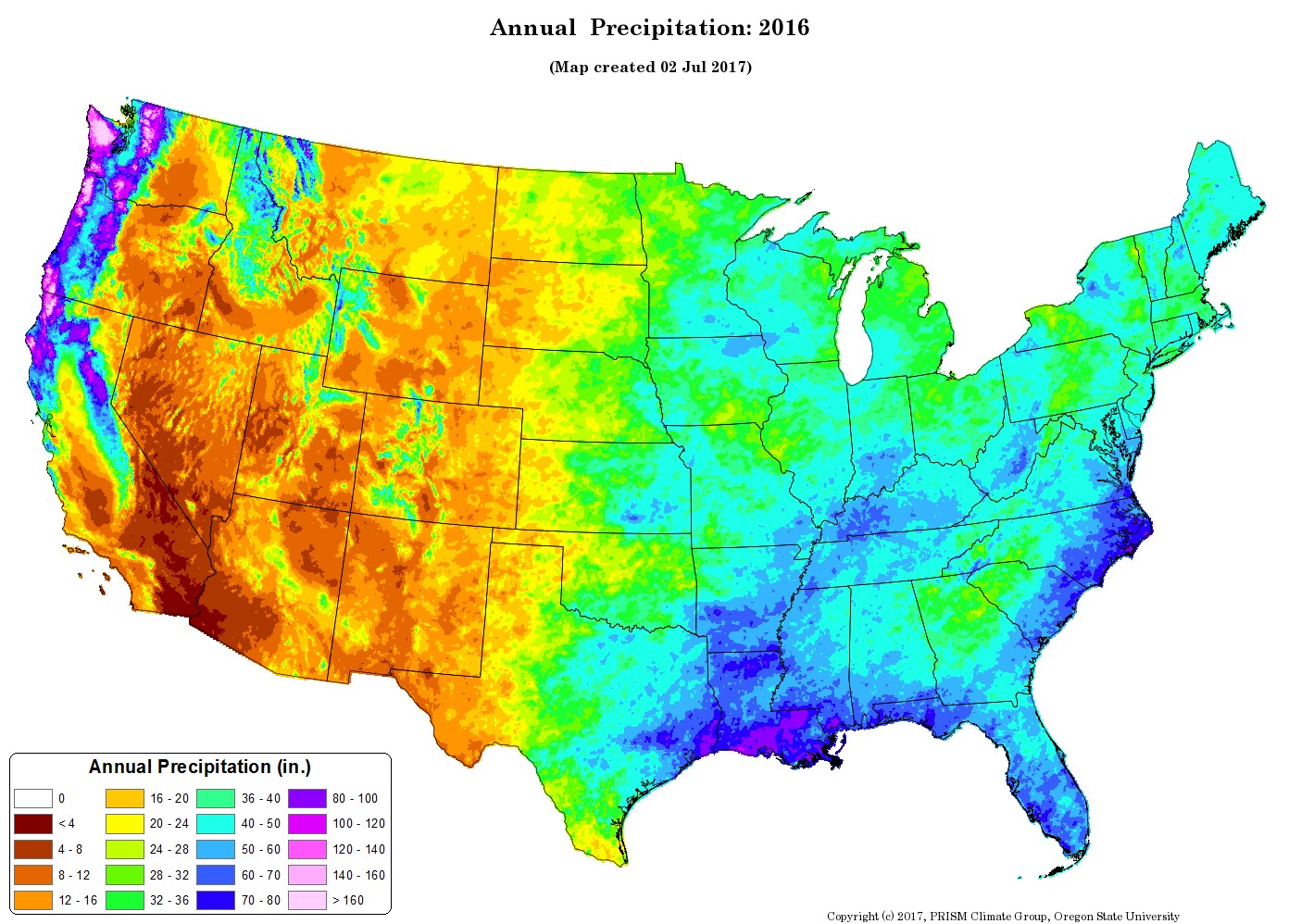

Warm temperatures are one of the region’s most defining characteristics. According to the Western Regional Climate Center, in Arizona "high temperatures are common throughout the summer at the lower elevations and temperatures over 125 degrees F have been observed in the past”. The southwest region also records relatively low annual precipitation totals, averaging less than 12 inches of rainfall in the past year.

Figure 2: PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University

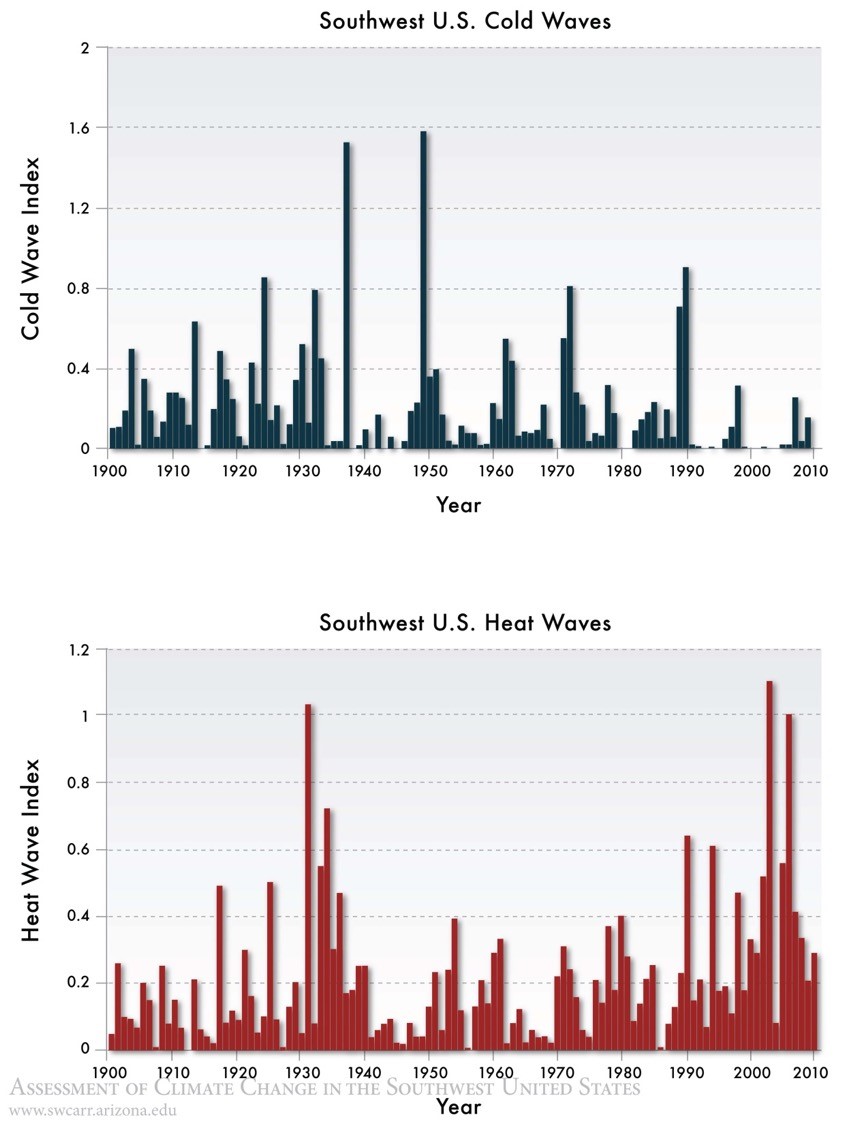

A large percentage of precipitation that does fall occurs as intense rainfall during the monsoon (Jun 15 – Sept 30). Current projections for the future climate of the Southwest including forecasts of gradually warming temperatures, more frequent and intense heat wave events, and increased uncertainty about precipitation along with increased incidence of drought.

Figure 3: Assessment of Climate Change in the Southwest United States

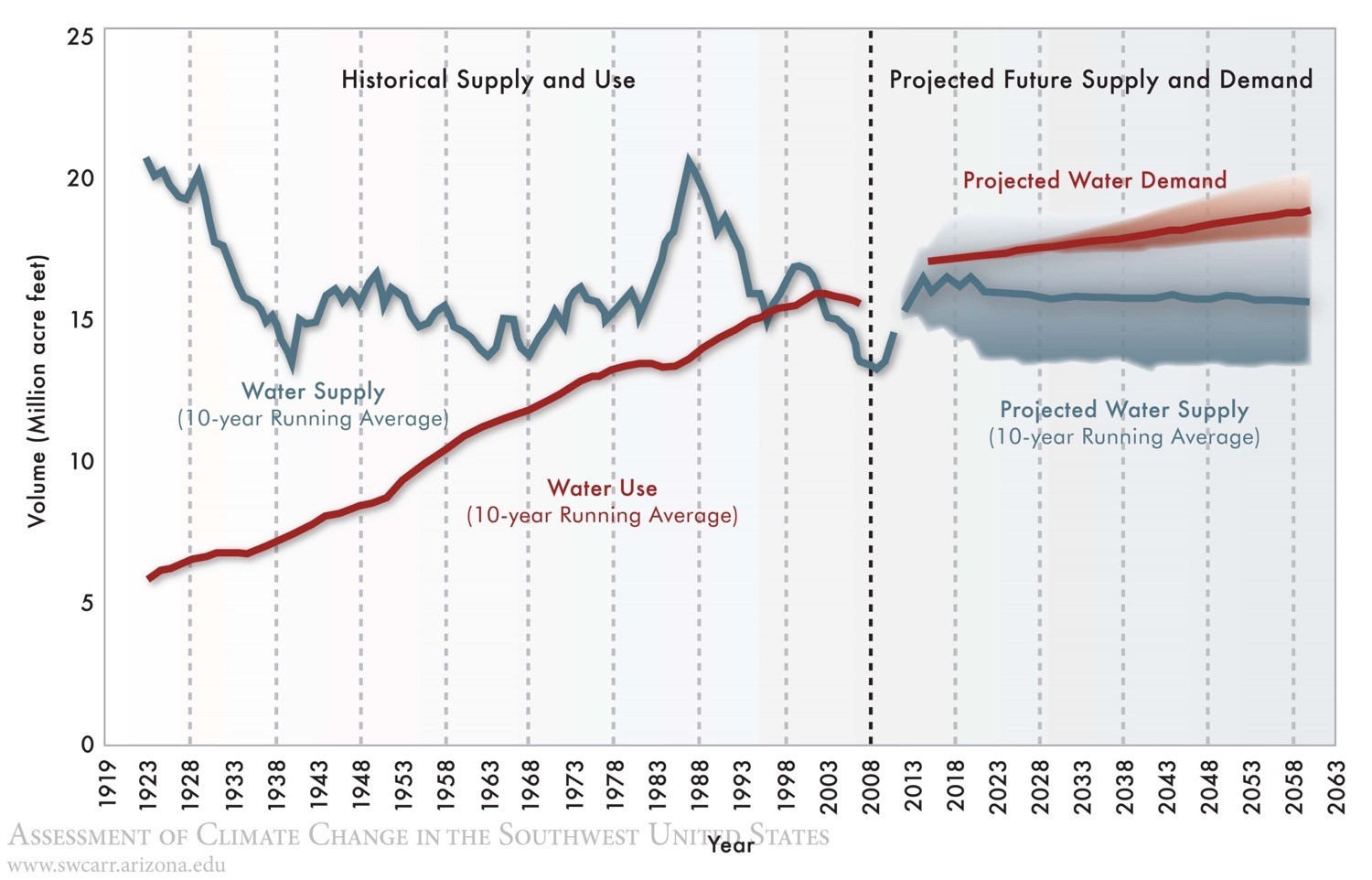

Population growth and competition over water resources places increasing demands on existing water supplies, which are subject to demand from end-users and fluctuating levels related to temperature and precipitation patterns. In order for the Southwest to increase its capacity to respond effectively to future changes in climate, the region must begin to integrate innovative solutions that support sustainable development.

Figure 4: Assessment of Climate Change in the Southwest United States

Climate Adaptation Strategies: Green Infrastructure

Sustainable development has grown in popularity as cities in the southwest are increasingly looking for new strategies to assess and respond to the anticipated future climate and environmental changes. Preliminary approaches for implementing sustainable development first begin with understanding the regions’ climate; there first needs to be a clear understanding of what is causing the problem in order to move forward and address the larger issues. For the Southwest, an issue that has become a priority concern is the increased frequency of drought from warming temperatures due to climate change, and how that will impact the supply of water in the near future. In order to conserve water, communities in arid and semi-arid climates are increasingly recognizing green infrastructure as a cost-effective approach that conserves water and also manages stormwater.6

Green infrastructure refers to a set of practices that mimic natural processes to retain and use stormwater. By promoting infiltration, evapotranspiration, and harvesting throughout the landscape, green infrastructure preserves and in some cases restores natural water balance.6 Commonly referred to as a Low impact Development (LID), the system consists of soils and vegetation that are used to manage stormwater through mimicking natural flow of water and use it for multiple benefits for both the environment and community. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a list of different G.I. elements that can be woven into a community, ranging from small scale to large scale elements spanning entire watersheds. Strategies that are commonly seen in metropolitan regions such as Tucson include rainwater harvesting collection systems (cisterns), rain gardens (also known as bioretention and bioinfiltration), bioswales and green streets (combination of street curb cuts and bioswales) (See .

Image 1 (above): Original Street Curb Cut, source: Harvesting Rain Water. Multi-use rain-garden plant lists: Invitations to Deeper and More-connected relationships

Image 2 (below): Street Curb Cut After Improvements, source: Harvesting Rain Water. Multi-use rain-garden plant lists: Invitations to Deeper and More-connected relationships.

When implemented properly, green infrastructure has the potential to create more resilient communities and further strengthen their ability to respond to climate vulnerability. In order to be effective however, a city’s green infrastructure initiative must incorporate different guiding principles, one of which includes place-based approaches. Place-based projects are site-specific and community based. Implementation of such projects incorporates the community with stakeholders and these dual partnerships engage to ensure the planning process recognizes distinctions within a city across ecological, social and cultural dimensions.1

City-led Initiatives and Non-profit collaborations

The Southwest has a great capacity to respond to these alarming environmental stresses and to lead in ensuring stewardship with natural resources. One city within the Southwest that has already implemented place-based approaches regarding green infrastructure projects is Tucson. Tucson has established the Framework for Advancing Sustainability program where its intent is to create a decision-making framework that explicitly considers sustainability and facilitates sustainable development within the community. Under this framework, specific goals have been designed to address climate adaptation, which include the following:

- Encourage public and private action in support of resilient social and economic systems that can withstand the stress induced by anticipated climate change impacts within the region

- Provide outreach and education to the community to enable individuals and groups to take action to improve the sustainability of Tucson

A non-profit organization that is leading in implementing these goals is the Watershed Management Group. Watershed Management Group (WMG) is a Tucson based organization that has developed community based solutions that ensure long-term prosperity of people and the health of the environment. Most of the projects they develop include the ability to provide people with the knowledge, skills, tools, and resources needed to create sustainable livelihoods. They have identified the value in stormwater management through landscape design and have further implemented green infrastructure projects throughout the city of Tucson to conserve water and mitigate flooding while at the same time, educating the public realm. Their most notable work includes their Green living Co-op, their Green Streets Program, their Advocacy and Public Policy through the Community Water Coalition, and their 50 Year Program to restore Tucson’s free flowing rivers.

WMG’s work has led to direct impacts on the Tucson community. Their Green Streets Program builds partnerships with different companies, non-profits, neighborhoods and municipalities and encourages collaboration efforts between them to install green streets. Green streets help conserve water, reduce urban flooding and stormwater pollution while at the same time, lessening the urban heat island effect. In short, G.I. presents an opportunity for communities to partner with non-profits to make a significant impact in response to climate change. G.I. has a direct impact on climate change.

Direct impacts is seen in one of WMG’s large-scale projects, whom they partnered with the Pima County Regional Flood Control District (PCRFCD) to solve the flooding challenges faced by residents in an area south of the Airport Wash. G.I. retention capacities were assessed using 2-dimensional hydrological models for three different watersheds. Results showed that by implementing G.I. throughout the watersheds in a 25-year scenario would lead to $2.5 million dollars of annual community benefits as a result from of flood reductions, water conservation, property value increase, reduced urban heat island impacts.9 A cost benefit analysis was also included to assess the full range of benefits throughout the area south of the Airport wash.

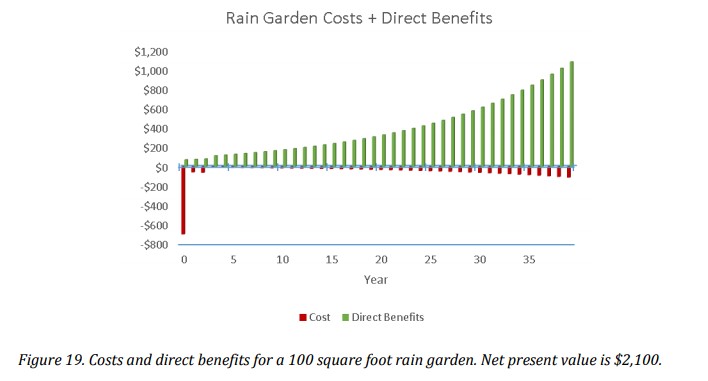

Four main practices were evaluated for the cost benefit analysis (CBA): rain gardens, rain gardens with curb cuts, rain garden retrofits and green street water harvesting features. The benefits for the CBA were based on the inputs of the number and average size of trees planted, area of water-harvesting basins, and volume of water-harvesting basins. A graph of a 35-year projection of a rain garden cost and direct benefit showed conclusive results. For a 100 square foot rain garden, although the cost in the first year was over $600, by the end of 5 years, direct benefits would outweigh the costs significantly. After 10 years, revenue would increase exponentially.

Figure 5: Watershed Management Group pdf.

Future considerations

Different parts of the Southwest are experiencing drier and hotter conditions, much of which is attributable to climate change. As severe drought events are further depleting the current water supply, cities will find compelling reasons to explore alternatives to meet water demands7. In order to meet the needs of current water supply and demand, climate resilient strategies will be vital for the near future projections. One climate resiliency strategy that has shown tremendous benefits is G.I. G.I. describes an approach to managing stormwater, where vegetation is used to capture water and through the process of infiltration, water is stored below ground surfaces and later reused. In our current built environment, many homeowners use drinking water to irrigate their lawns. By implementing rain water catchment systems, potable water usage is ultimately reduced, which consequently leads to lowering the stress on the demand for water supply. Other benefits from G.I. practices include the ability to create greater air movement, reflection of heat, and provide shading that can cool urban environments.

Although stormwater management through green infrastructure may have many benefits within different climatic regions, there still exists overseen setbacks and barriers. One of the biggest barrier is the lack of funding. At least at the federal level, there is no single source of dedicated federal funding to design and implement green infrastructure solutions. Without assistance, communities take several approaches to financing wastewater and stormwater projects through the use of municipal bonds10, which may not always be the best alternative. However, there are a few helpful resources, such as the EPA’s financing options and resources for local decision-makers report, that discuss both pros and cons for several sources of funding for small-scale projects. Other barriers include the lack of information on performance overtime and cost-effectiveness, the uncertainty of water quality improvement and the maintenance required to maintain these systems over time.

References

- Brown, Hannah J. (2017). Green Infrastructure: Best Practices for cities. U.S. Green Building Council. Advocacy and Policy section.

- Pagnet.org. (2017). Green Infrastructure. (online) Available at: https://www.pagnet.org/Default.aspx?tabid=189. Accessed 19 Nov. 2017.

- AdaptationClearinghouse (2008). City of Tucson, Arizona Framework for Advancing Sustainability. (online) Available at: http://www.adaptationclearinghouse.org/resources/city-of-tucson-arizona…. Accessed 19 Nov. 2017.

- MacAdam, James, T. Syracuse, J. DeRoussel, and K. Roach. (2012). Green Infrastructure for Southwestern Neighborhoods. Watershed Management Group.pdf.

- Garfin, G., A. Jardine, R. Merideth, M. Black, and S. LeRoy, eds. (2013). Assessment of Climate Change in the Southwest United States: A Report Prepared for the National Climate Assessment. A report by the Southwest Climate Alliance. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Liverman, D., S. C. Moser, P. S. Weiland, L. Dilling, M. T. Boykoff, H. E. Brown, E. S. Gordon, C. Greene, E. Holthaus, D. A. Niemeier, S. Pincetl, W. J. Steenburgh, and V. C. Tidwell. (2013). “Climate Choices for a Sustainable Southwest.” In Assessment of Climate Change in the Southwest United States: A Report Prepared for the National Climate Assessment, edited by G. Garfin, A. Jardine, R. Merideth, M. Black, and S. LeRoy, 405–435. A report by the Southwest Climate Alliance. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Green Infrastructure in Arid and Semi-Arid Climates: Adapting innovative stormwater management techniques to the water-limited West. (2009). Retrieved from https://www3.epa.gov/npdes/pubs/arid_climates_casestudy.pdf

- Lancaster, B., J. MacAdam, J. Miller, K. Roach, C. Shipek, L. Shipek, J. Silins, S. Somnath, T. Syracuse. (2011). The Ripple Effect Annual Report. Watershed Managent Group.

- (2015). Solving Flooding Challenges with Green Stormwater Infrastructures in the Airport Wash Area. Watershed Management Group in collaboration with Pima County Regional Flood Control District. Pdf.

- Copeland, Claudia. (2016). Green Infrastructure and Issues in Managing Urban Stormwater. Congressional Research Service